Sherlynn Reid was the first African American to serve as Director of Community Relations for the village of Oak Park, a post she retired from in 1999 after 22 years. She was also a diversity pioneer, activist and member or leader of numerous civic, educational and religious organizations.

Born in Pittsburgh, PA, she graduated from Fisk University where she studied arts and drama. She later met and married Henry Reid, a sociologist. After stops in Cleveland and Detroit, Sherlynn, Henry and their three daughters, Mary, Dorothy and Lorie, moved to Oak Park in 1968. They were the first African American family to purchase a home through a realtor, shortly after passage of the village’s landmark Fair Housing Ordinance.

Sherlynn Reid is best remembered by those who knew her well. One of those people is Ken Trainor, an editor and columnist for Oak Park’s Wednesday Journal (WJ) newspaper. In 2019, the Oak Park River Forest Museum awarded its Heart of our Villages Award to Reid; Trainor delivered this tribute at the award ceremony, and in his subsequent WJ column following her death:

_ _ _ _ _ _ _

Remembering Sherlynn Reid

Sherlynn and Henry Reid made history when they moved to Oak Park in 1968. They were the first black couple in the 1960s to buy a home from a realtor using a conventional loan — which happened just after the adoption of the village’s landmark Fair Housing Ordinance. Sherlynn talks about that era in Joe Kreml’s video in the Fair Housing exhibit at the Historical Society’s Oak Park River Forest Museum.

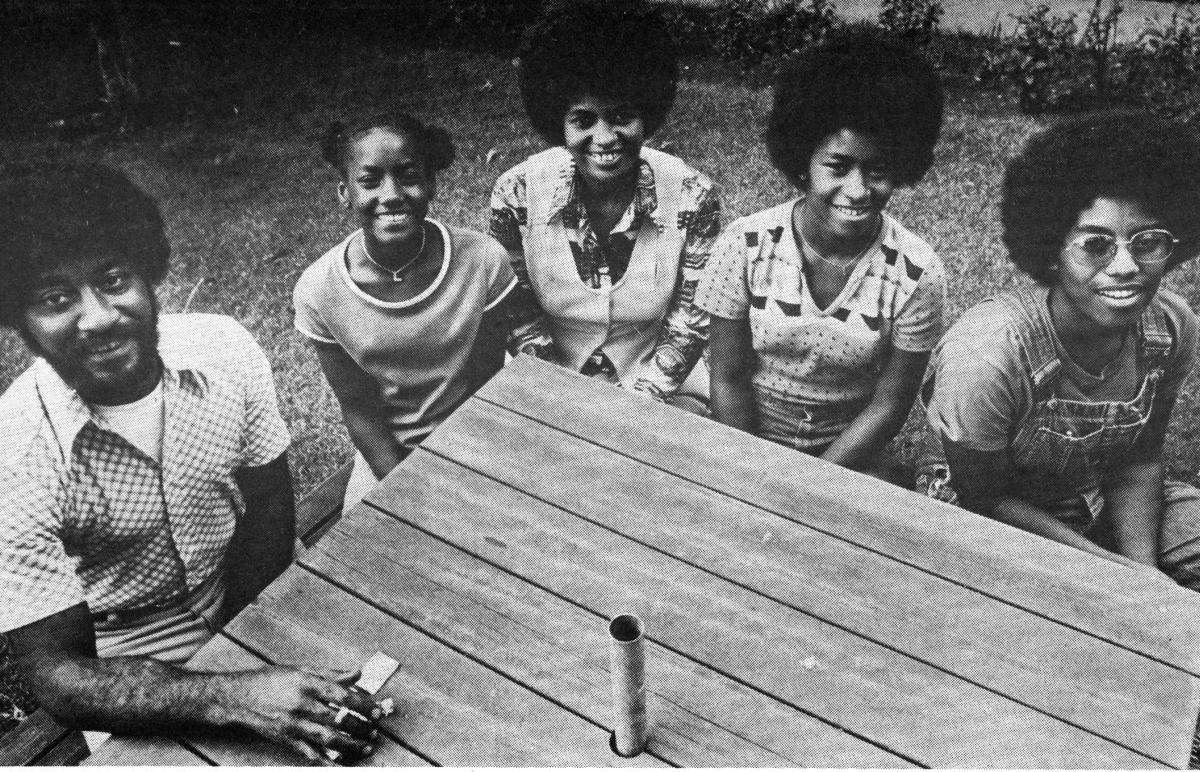

The Reids, along with the Robinets and the Registers, the 3 Rs of Oak Park integration, were the pioneers who paved the way. And so were Sherlynn’s three daughters, Mary, Dorothy and Lori who helped integrate OPRF High School.

The first thing Sherlynn did when they moved into that big house on Ridgeland Avenue was call Police Chief Fremont Nester and tell him he could remove the squad car from in front of her home, which was assigned as protection against, well, people with anger issues and poor impulse control.

Sherlynn wasn’t worried. She told the chief they would take their chances, which sounds like a good motto for Black Oak Parkers: They took their chances.

The next thing she did was get involved, quickly weaving herself into the community fabric. She joined the First Tuesday Club, a group of remarkable women — including Joan Pope, Marge Greenwald, Ann Armstrong, Fran Sullivan, Bobbie Raymond, Trudi Doyle, Marie Kruse, Mary Ellen Matthias, Gloria Merrill, Sandra Sokol (and no doubt others) — who networked, researched issues, and started waking up a sleepy suburb.

By 1999 when Sherlynn retired after more than two decades as head of the village’s Community Relations Department, she had served as chair of the League of Women Voters’ Human Relations Committee, established a human relations workshop at OPRF High School, joined the Beye School PTA board, the Christian Education board at First Congregational (now First United) Church, was a Brownie Troop leader and served on the Girl Scouts Council.

Actually, she did all that in her first three years here.

She eventually got around to being president of the League of Women Voters and the 19th Century Club; was an active member of two African-American social organizations, Jack & Jill, and Links; helped launch the block party tradition in Oak Park; and started the “Dinner & Dialogue” program through the Community Relations Dept. to increase the comfort level between white and black residents. She was also a longtime supporter of the CAST arts program at Julian Middle School, which her husband Henry co-founded, and also the scholarship fund for that program, which bears his name. She even acted in some of the plays. And she was a member of the task force that founded the Oak Park Education Foundation.

She helped Oak Park come a long way from that grocery store where, according to a 1971 Oak Leaves article, a “gray-haired matron” came up to her and said, “Pardon me, Miss. I’m looking for domestic help. Can you spare a day for me?” And after speaking engagements when well-meaning members of the audience gushed, “You’re so different,” she would answer with the air of authority she naturally exuded, plus her a gracious smile: “There are thousands of black people exactly like me. I happen to be the only one you’ve met.”

Oak Park is a different, and much better, community than the one Sherlynn found when she arrived in 1968, thanks in no small part to her efforts.

In that same 1971 article, Henry Reid was quoted as saying, “Only whites can integrate a community. Blacks just desegregate it.” But Sherlynn did integrate this community, in the true sense of the word “integrate,” which is “to make whole.”

The Reids, the Robinets, the Registers, and many other black families and households helped make Oak Park whole. We have a long way to go, but thanks to pioneers like Sherlynn Reid, we’re going together.

As opposed to how Sherlynn was born, reportedly 2½ hours after her twin brother, Sherwood, emerged — with no one expecting her to show up. Her mother, Mary Dee, the first black radio personality in Pittsburgh, is rumored to have told the doctors, “It’s not over till it’s over.”

Well, Oak Park wasn’t expecting Sherlynn to show up either, but she got here none too soon — and definitely left too soon.

By the age of 86, she had slowed down some and her eyes were giving her trouble. But her vision was as keen and clear as ever. Here’s how she described that vision just before the Millennium:

“We must look at new paradigms where people of all races, professions, sexes, religions, sexual orientations, ages, etc. are determined to live side by side in tolerance, if not love, of one another.”

Sherlynn Reid did as much as anyone to make the new Oak Park paradigm a reality.

As Frank Lipo, executive director of the Historical Society, put it recently, “There is always a need for the Sherlynns of the world. She created systems of non-oppression.”

--- Ken Trainor, Wednesday Journal

Submitted by Michael Guerin, April 2021