During the first half of the Twentieth Century, the term “central heating” could be applied to an entirely different system than it is today. Instead of using individual heating units in single-family homes, businesses and individuals living in central Oak Park could get hot water heat from a single power plant. Called the “Yaryan System,” it is a prime example of an emerging technology undone by rapid development, consumer complaints, and the increasing political power of energy companies.

Developed by H.T. Yaryan of Toledo, OH, the “Yaryan System” had a simple premise. A coal-fired steam engine powered a generator to produce electricity for distribution to homes and businesses. A byproduct of the steam engine was considerable heat, which could be used to heat water that could be pumped through underground pipes to radiators in the same homes and businesses. A single generator could heat hundreds of homes at a very reasonable cost.

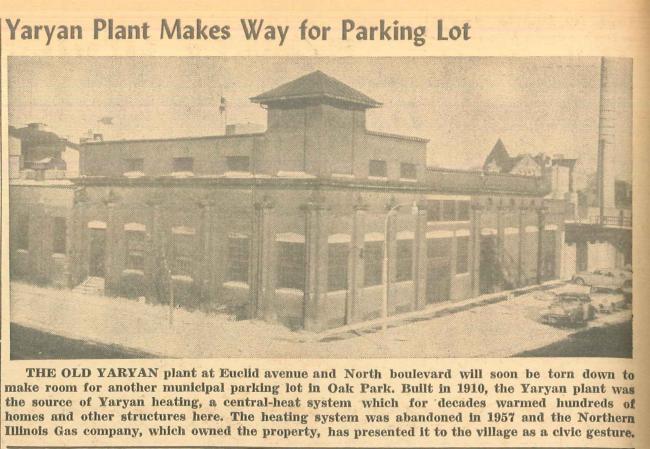

In 1900, three delegates from Oak Park had traveled to Evanston, IL, where the Yaryan system was being used. A year later, the “Oak Park Light, Heat & Power Co.” constructed a generating plant, designed by E. E. Roberts, on the northwest corner of Euclid Avenue and North Boulevard. A well was dug and a network of underground water pipes was laid connecting customers to the system. These pipes eventually extended throughout central Oak Park—generally from Harlem to East Avenues and from Madison Street to Chicago Avenue, with three short extensions north of Chicago.

Generally, customers were quite happy with the Yaryan system. They didn’t have to install their own furnaces, buy their own coal, feed the furnace, or clean up the mess created by coal dust. Village buildings were heated free of charge! Moreover, the Yaryan system worked extremely well. Customers often had to open windows in winter to lower the temperature inside the house. But because the system was fixed to the size of the original house, any additions had to have a separate heating system.

As Oak Park’s population continued to grow and new developments were planned, demand soon outstripped the capacity of the existing plant, with no way to expand it. The Village Board regularly received complaints from residents that the company was refusing them service. Worse, as more efficient steam turbines replaced steam engines to power electric generators, the Yaryan system became more expensive to operate, resulting in several proposed rate hikes. Not surprisingly, these rate hikes were contested, sometimes bitterly.

By 1912, the Yaryan plant was acquired by the Public Service Company of Northern Illinois, which was unwilling to upgrade the system. Over time, customer numbers declined; by 1956, there were only 588 customers. The equipment and infrastructure had become less efficient and eventually obsolete. Finally, despite furious protests, the Yaryan system was shut down in 1958 and the plant was demolished the following year, to be replaced by a parking lot.

The closing of the Yaryan plant created problems for homeowners. Houses designed for the Yaryan system lacked space for furnace rooms and sufficient insulation for other systems. Many, if not most, didn’t even have a chimney and converting to conventional heating was costly and difficult, despite a partial indemnification from the Public Service Company. But the Yaryan system was an early example of redirecting energy that would otherwise have been lost, and resulted in a clean, economical heating system.

Submitted by John Borland and Mary Ann Porucznik, September 2022

Sources: Oak Park Argus, March 29, 1901; Oak Park Reporter, April 4, 1901; WPA Historical Survey of Oak Park, Illinois, 1937; Oak Leaves—March 27, 1903, Jan. 22, 1959; Dec. 10, 1959; Wednesday Journal, Jan. 4, 1984; Frank Lloyd Write Home & Studio Volunteer Newsletter, September 1989